Fundamentalization as the Blighted Root of Common Sense Morality

An interdisciplinary inquiry, with brainrot

In a comprehensive meta-analysis published in a 2005 edition of the Psychological Review, van Nostrand and colleagues show that if you’re scared of public speaking, you should picture the audience naked. This is no easy feat of imagination, and so notwithstanding the mountains of evidence adduced in support of this conclusion, it has proven difficult for most people to put into practice…

…until now. In late 20x6, Pfizer and colleagues will bring to market a pill that promises to make this “picturing” as easy as pie for anyone with an esophagus and a glass of water or Gatorade or something. There is only one side-effect, although “side” is maybe a bit of a stretch: The pill works its magic by inducing in the swallower a full-fledged belief that everyone in the audience is indeed stark naked. Phase 3 trials show a remarkable 78% increase in public speakingness; however, this is coupled with a 70+/-1% increase in the probability of getting naked oneself (among Continental philosophers) and a beth-2 percent increase in the chances of reporting the entire audience to Platonic HR (among analytic philosophers).

This pill…………dear reader………….is like………....MORALITY.

.

..

…

….

…..

……

Ugh, okay, Referee 2; I guess I have to explain everything! But when Tom Hurka comes to you inveighing against overlong journal articles, don’t come crying to me.

The pill is a mechanism that was selected — in this case, by Pfizer and sons — for the advantages it confers in public speakitude. But it is a blunt instrument, for it confers these advantages by inducing not a mere imaginative state which can be quarantined from the rest of the swallower’s mental life so as to forestall any doxastic and nakedness disadvantages, but a belief with the characteristic functional profile thereof. This is not because Pfizera is malicious, but just because such a pill is cheaper and easier to manufacture. And so we’re left with only two options — stay nervous in front of the audience, or induce in yourself the full-fledged belief that its members are naked.

Well, the more I’ve read in the psychology, evolutionary biology, and neuroscience of moral thought in the last couple of years, the more I find it plausible that the mechanisms that give rise to common sense, deontological, *cough* WRONG *cough* moral beliefs are a lot like this pill. They select for something to serve certain purposes unrelated to the apprehension of truth (in this case, about fundamental morality), but owing to considerations of efficiency and economy, the thing they select for is a belief that certain deontological constraints are fundamental moral truths — rather than, say, beliefs to the effect that deontological principles are good rules of thumb, or that it’s wiser to blame and punish people for violating deontological constraints than for violating consequentialist ones.

I call a process “fundamentalizing” iff. it selects for beliefs regarding fundamental morality in response to factors that do not seem relevant to fundamental rightness/wrongness/reasons. By fundamental rightness, etc., I mean rightness that is not explained by anything else. It’s what, ultimately, most philosophers working on normative ethics are ultimately after. To think that something is fundamentally right, then, is to either think that it is right and that its rightness is not explained by anything further, or to think that it is right, and not be disposed to think that its rightness is explained by anything further.

Now, my sense is that there's no settled theory or set of theories about how deontological or any other moral judgments come about — more like a lot of plausible contenders. But I think we can say something philosophically interesting before we've reached the end of psychological inquiry.

Model-Free Reinforcement Learning

Fiery Cushman and Molly Crockett have independently suggested that we might explain characteristically consequentialist and characteristically deontological moral thinking in terms of "model-based" and "model-free" reinforcement learning, respectively.1 Both kinds of learning involve the assignment of value or disvalue to representations on the basis of feedback from the environment. The difference: Systems of model-based learning, the cognitively costlier kind, construct causal models of the world, incorporating actions and consequent states; then in responsive to perceiving a state as aversive, they assign value to a representation of that state, and then only indirectly to a representation of the action upon which it counterfactually depends. Systems of model-free learning do not construct a causal model; rather, they respond to perceptions of states as aversive by assigning (dis)value to representations of actions regarded as giving rise to those states. In other words, a model-based system encounters an apparently bad state and provisionally concludes "the state is bad; avoid behaviour insofar as it leads to this state"; a model-free system encounters the same and provisionally concludes "the action that led to this state is fundamentally bad; avoid it".

Already you can see why a model-free system is potentially fundamentalizing. It has only one way to adjust in light of an apparently aversive state — assign greater disvalue to the representation of the action that the thinker regards as giving rise to that state. A blunt instrument, in other words. However, fundamentalizing is not simply the assignment of fundamental moral value. It's the assignment of fundamental moral value in response to factors that seem irrelevant to it.

But it seems to me that model-free reinforcement learning, in humans at least, is guilty of this on many counts. You might wonder how such a system is supposed to yield deontological verdicts. After all, suppose we just focus on the doing/allowing distinction for a moment; bad states can counterfactually depend on doings just like they can depend on allowings, so why wouldn't such a system devalue representations of such allowings just as they devalue representations of such doings? I think there are several promising answers to this question, but for brevity’s sake I’ll focus on two:

(1) We as philosophers are all too familiar with the dependence of bad outcomes on omissions; we know about the pond and famine and the trolleys and all of that. But this is not so apparent to young moral learners. Rather, infants and young children are confronted with myriad instances of "positive behaviour" associated with aversive outcomes, but vanishingly few instances of "negative behaviour" associated with the same. Lots of hitting and biting and pushing among toddlers, not so many proto-Michael Phelps’s fiddling while the other kids drown. And so the model-free learning system devalues actions upon which bad outcomes depend (hereafter: “harmful actions”) much more than it devalues omissions upon which they depend (hereafter: “harmful omissions”). But insofar as this is part of the explanation of why we tend to think that harmful actions are, all else being equal, fundamentally worse than harmful omissions are, we should be suspicious of this tendency; this because the frequency with which a type of behaviour is causally associated with bad outcomes in early childhood seems irrelevant to the wrongness of any token of that behaviour.

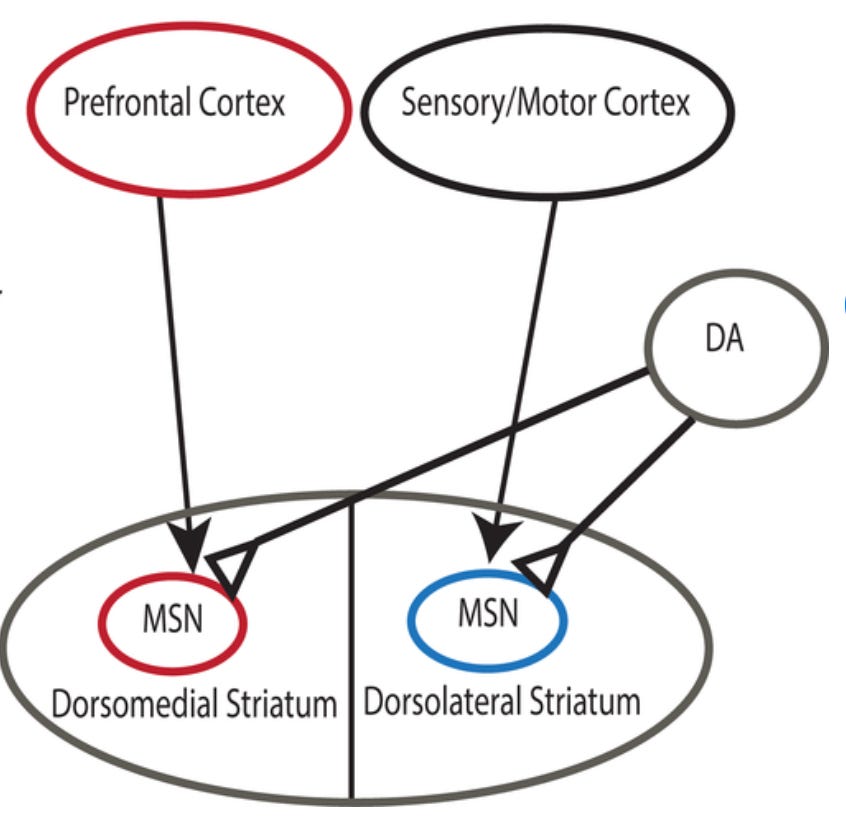

(2) A different explanation, not inconsistent with (1): Reinforcement learning is implemented in humans as a "loop" involving dopaminergic neurons in the striatum, and the parts of the cortex responsible for action representation. But different parts of the cortex are involved in model-based learning than are involved in model-free learning.2 The former incorporates the prefrontal areas of the cortex, which are capable of representing action with a great deal of abstraction and syntactic complexity — conjunction, negation, etc. The latter, however, incorporates the sensorimotor cortex, which seems to be capable only of simple, concrete representations of action — as hitting, pushing, etc.3

This provides fodder for an explanation of our tendency to judge harmful actions like hitting and pushing as worse than harmful omissions, whether we think of the latter as "not rescuing from the quicksand", say, or as "doing A or B or C or D...", where A, B, C, D and so on are alternatives to rescuing from quicksand. The latter sorts of representations are just not available to be stamped as “good” or “bad” by the cortical-striatal mechanism responsible for model-free learning in humans. This makes sense from the point of view of computational ease and efficiency, which is the main advantage that model-free learning has over model-based learning. But this sort of representational limitation does not seem to be of fundamental moral significance, or, on the face of it, connected to anything that is. I think that if we were to encounter an alien species whose moral judgments reflected the fact that its moral learning occurred via a system incapable of representing actions that involved, say, the use of both arms simultaneously, we would expect those judgments to be systematically off-track.

Evidence and Punishment

Here is a rather different explanation of our tendency to judge harmful actions to be worse than harmful omissions. I don't regard it as inconsistent with the reinforcement learning explanation; both could be at work. There is an evolutionary advantage to (a) avoiding punishment, and (b) participation in successful punishment, and on the other hand, a disadvantage in attempting, unsuccessfully, to punish. Peter deScioli, Rebacca Bruening, and Robert Kurzban have hypothesized that one is less likely to face punishment for harmful omissions than for harmful actions, and that it is easier to participate in successful punishment of harmful actions than for harmful omissions — and that this all helps to explain why we tend to regard the former as fundamentally worse than the latter. That’s because harmful actions tend to leave behind obvious and public evidence, while harmful omissions do not. The availability of evidence mediates punishment, especially because punishment, to be successful, must be done by groups rather than individuals, and it is difficult to get a punishing group together without publicly available evidence.

But again, if this is part of the explanation of why we think harmful actions are fundamentally worse than harmful omissions, then we have grounds for suspicion of this judgment. There doesn't seem to be any tight connection between the availability of evidence that someone did something, and the wrongness of that thing. Crimes that are poorly covered-up are not for that reason more heinous. Now, if this differential leaving-behind of evidence gave rise only to judgments like “It’s a better idea to punish people when there’s more evidence that they did something harmful, and better idea to stay the hand when the evidence is weaker”, then it wouldn’t be a fundamentalizing process. But if, as deScioli and colleagues suggest, the explanans is the ordinary deontological judgment that, as a matter of basic morality, harmful doings are worse than harmful allowings, then the process does appear to be a fundamentalizing one.

Now you may reply: "Look, you're saying there's no connection between fundamental wrongness and availability of evidence, or fundamental wrongness and amenability to simple motor representation, or fundamental wrongness and frequency with which the type to which it belongs being associated with aversive outcomes in early childhood. But doing harm is in fact more wrong, fundamentally, than allowing harm is, and so insofar as processes that are sensitive to the aforementioned factors ‘spit out’ the common sense attitude regarding doing vs. allowing, it appears that these factors are connected to matters of fundamental wrongness after all.”

Of course, we’d look askance at someone who’d just taken the Pfizera pill and responded in like manner: “The audience is naked. Like, that’s a fact. So it turns out that this pill not only helps your öffentlichsprechlichkeit, but also reveals the truth about the nudity of the audience.” On the other hand, I think that it would be all but impossible to vindicate any moral system if we couldn’t avert to judgments about the truth of the beliefs that a mechanism “spits out” in assessing the truth-conduciveness of that mechanism. Ultimately, I think the apposite questions are: (1) How obvious are the moral judgments we offer in assessing the outputs of a developmental, evolutionary, or other process, and the ones we offer in assessing whether that process is apt to be truth-conducive?, and (2) How much “work” does the vindication of the process do in explaining morality? This is cryptic, but we will return to it in future posts, because my dopamine levels are low and so I want to post this now!

Crockett also assigns a role to a third, “Pavlovian” system. I should also say that she told me she gave up on this suggestion because neither she nor Cushman could find a way to demonstrate it experimentally. But that kinda harshes my vibe, so…yeah……

See, e.g., Melissa Sharpe, et. al., “An Integrated Model of Action Selection: Distinct Modes of Cortical Control of Striatal Decision Making,” Annual Review of Psychology 70, 2019, pp. 53-76.

See Marco Tettamanti et. al., “Negation in the Brain: Modulating Action Representations,” NeuroImage 43(2), 2008, pp. 358-67; Ann Nordmeyer and Michael Frank, “A Pragmatic Account of the Processing of Negative Sentences,” Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society, 2014; Moritz Wurm and Angelika Lingnau, “Decoding Actions at Different Levels of Abstraction,” Journal of Neuroscience 35(20), 2015, pp. 7727-35; Wurm et. al., “Decoding Concrete and Abstract Action Representations During Explicit and Implicit Conceptual Processing,” Cerebral Cortex 26 (8), 2016, pp. 3390-3401; Sharpe et. al. (2019).

Very nice!

There are some omissions people get lots of training about at a young age, like not saying thank you, and not sharing, and I think those things as a result get quasi-moralized.

But I like this idea - deontology is basically what happens when you learn like a simple behaviorist predicts, just by reinforcing actions, but it takes some more sophistication to associate good and bad with the outcomes.

Where do you see Tomasello’s work fitting in here, where he argues that people objectivize norms about how people around here do things?