TL;DR:

Universities are like religious institutions, and should strive to become more like them, because this will make them a stronger bulwark against “trashworld”. There’s also a more general point about conserving institutions as a way of safeguarding values that are difficult to articulate.

NTL;R:

Back during the pandemic, a University Education looked a lot like an off-brand MOOC. Whereas top-shelf MOOCs treated their customers to Michael Sandel’s honey-voiced, meticulously prepared incantations of the trolley problem, or Amy Hungerford’s breezy, Socratic unpacking of Barth’s Lost in the Funhouse, the University of Toronto pop-up MOOC (“velut arbor aevo”) gave their paying customers1 a weary, stressed-out father of two school-shuttered kids, who looked like a Steve Bannon impersonator forced to record a confession video — sometimes with bonus ASMR “mouth sounds” content if he hadn’t finished his lunch before class started.

And of course we all decried this gloomy state of affairs. No need to remind you. But I think that from a strictly pedagogical perspective, the gap between the MOOC-ified, pandemic-era university and an ordinary education at a University like mine — i.e. one with talented students and faculty, and not teetering on the brink of collapse but not terribly flush with cash, either — was not so great as was commonly supposed. I mean, is there really such a difference between in-person and virtual attendance of a class, if that class is a 500-person lecture? Sure there are some smaller classes, but more and more these are being phased out as inefficient, and it’s not clear that most students welcome or appreciate them. A brick-and-mortar university offers help for students who need it — tutoring, office hours, help with essays. But a lot of this can be done online, and in any case, I harbour doubts about the overall social value of all of this help, even if it’s good for the students who receive it. Let me simply ask: If a single mom masters Python all on her own, through an online course she takes after the kids go to bed, while a 20-year-old barely ekes out a gentleman’s B after loads of handholding and support and frantic late-night e-mails to the professor, do we really want a system that tells the world that what he did is better than what she did? Indeed, one could be forgiven for thinking that many universities function as remedial education for the privileged or unburdened, who can pay not only for that remedial education, but for the labelling of it as advanced education.

To be sure, I’m overstating things for dramatic effect restacks. For example, I do think that for someone who’s seriously interested in improving their philosophical work, an hour shooting the shit with me or one of my colleagues gives you something you can’t get from a MOOC, or a book, or a subreddit. But in this essay, I’d like to explore whether the university is valuable in certain other ways that are either less obvious, or less comfortable to talk about.

My focus is on the traditional American-style university, and will apply to universities elsewhere/elsewhen to the extent that they resemble the same. To certain cast of mind, the TASU looks like a deeply weird institution. Imagine the pitch: “So the idea is for a school, right? — but not like high school. This is… higher education.2 But ‘higher’ maybe not so much when it comes to, y’know, learning and the whole bit. Some of the classes are twenty times as big as high school classes. And you don’t have to attend them. And remember how your high school teachers were trained to teach, and loved to teach, and were incentivized to teach, and looked like they’d seen the sun? Yeah, well these cats are different. This one’s teaching you because she refuted the modal ontological argument; that one is an expert on Ancient Persian trade routes. Oh yeah, and they can’t be fired. Ok, scratch that — it’s specifically the ones who care about teaching the least: they’re the ones that can’t be fired. And remember all that stuff about “healthy school lunches” and “you can’t drink and do drugs in school”. Not here, baby! Also, a lot of antibiotics and SSRI’s being prescribed because, y’know, school. And you like sports? Stay with me here: What if we brought pro-quality athletes to school, and their coaches made millions of dollars, and we spent millions of dollars on facilities that only they could use, and then they also attended your classes. How cool would that be? And musicians would come! And therapy dogs. And military training. And there’s a chapel…somewhere…And when you graduate, keep coming back for the sports, okay? And while you’re back, we could use a couple bucks…”

Quite a motley collection of features, as many critics of the traditional American university have noted. Certainly if any MOOC tried to follow suit — maybe Coursera joining forces with Tinder and DraftKings and Doordash and Calm and Hallow, and yeah, I don’t even know — that would strike most people as mission creep, or rather, as steering the mission off the Salginatobel Bridge.3

But I don’t think the value of the university inheres in serving a narrowly defined role. I think it is at its best precisely when it functions as an organically-assembled collection of mutually-reinforcing aspects that, together, provide an arena in which a person can live a complete life — learning, playing, praying, fucking, crying, competing, thriving, and struggling; touching the sacred and the profane; rejoicing in beauty and in gallows humour. A university is supposed to serve as a whole life-world, and a model for future whole life-worlds, for a whole person. It is supposed to function in many ways like a religious institution — and indeed, of course, many of the oldest American universities were sectarian religious institutions, and still are, nominally. A church is not just a place to learn the contents of holy texts, say “yep, got it!”, and go home. Centrally, there is prayer, and liturgy, and song, and discussion. It is common, and used to be far more common, to date and court and marry within your church. The aesthetic features of the church serve to orient you towards some conception of the divine. There are church picnics, and Sunday schools for the kids; parents host birthday parties for their children in their church basement. And I think the confluence of these myriad, mutually-reinforcing features conduces to the success of the church, and a collection of similar ones to the success of the university. We need knowledge, and beauty, and playfulness, and romance, and awe, and the strongest institutions are ones that deliver the whole package — a whole life-world, gearing towards whole people with their multivarious longings.

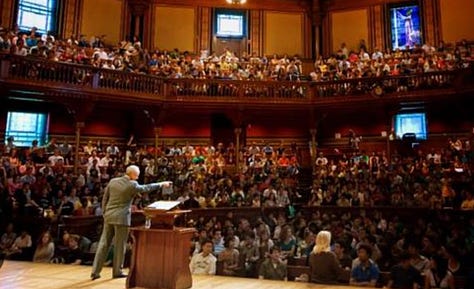

A snapshot: I remember sitting in Princeton’s majestic McCosh 50 in my sophomore year, watching a young Gideon Rosen entertain a query or objection from a student — whom he called, as he invariably did, “the questioner”. Rosen’s lecturing style was sermonic in many ways — theatrical, and above all else, absolutely dead serious. He spoke like he was debating the devil for humankind’s souls. And he looked, I don’t know how else to say it — like a professor, constantly flipping his hair to one side and rolling his sleeves up, fussing over his person as he fussed over the argument, because we fuss over things that are no joke. And McCosh 50 looked like a lecture hall — rows of old wood and iron desks, sunlight pouring in from stained-glass windows, angelic chandeliers, wood, like, uhh, arches? in the ceiling, designed by Robert Maillart.4 When I was a student, it was, by far, the most popular lecture hall for students to streak. And I wanted to be like him, in a place like this. Rosen represented a way of being an attractive, compelling, respected man, and that McCosh 50 represented an institution and a way of life that was esteemed. And people want to be attractive, and they want to be esteemed, and they want fun, and glory, and community. And institutions that pay heed to this thrive, and those that don’t are forced to toss money at PR firms every five years in an attempt to paper over their self-delusion about what moves us.

But why does it matter whether the church, or the university, or any other institution thrives, exactly? Why, for instance, does the loyalty of the people to a city-state, their willingness to sacrifice for each other and for the state, matter? Sometimes it’s because of threat from invaders from another city-state. Sometimes because a natural disaster forces them to rebuild. At some points in history, the university would have been valuable largely as a counterweight to religious fundamentalism, or fascism, or communism. Now I think it is valuable as a counterweight to another civilization-within-a-civilization that looms ever larger on the horizon — a rising hegemon that I call “trashworld”. Most of you are more familiar with trashworld than you’d like to admit.

Trashworld is hustling, and entrepreneurship, and being a high-value man, and smash that subscribe button, and women are trying to trick you, and you’re arguing based off emotion but I’m arguing based off logic, and the smartest man in the world just said God exists so there, and women should be quiet and subservient, and I’m looking for a provider who will open doors for me, and Marcus Aurelius, and stoicism, and stoicism for dummies, and how stoicism will get you rich and how stoicism will get you laid, and did I mention I don’t argue based off of emotion, and this influencer is mad at this influencer who’s mad at this influencer, and debate me bro, and you’re sealioning and you’re gaslighting, and trauma, trauma, and “trauma”…5

If you’ve spent time on the internet, you’re probably familiar with trashworld and its “content”. What is the core of trashworld? Money? Cars? “Content”? It’s all very transactional, and arriviste, and, well, trashy — and certainly, shot through flattening generalizations about men and women. But if I were to pick one unifying feature of trashworld — and this is never stated, but comes through crystal-clear in behaviour — it’s that other people’s immediate approval, or even just attention, is the measure of all things. There’s no “It’s not popular and most people won’t even understand it, but it enriches us morally or spiritually, and that justifies it.” There’s no “This philosophy or self-help makes you a better person, even though it won’t make more people like you or want to sleep with you.” The entirety of trashworld seems to be modelled on the telos of the influencer — get as many eyeballs, as many clicks, as possible, or whatever the pale yellow imitation of that is in the (snarf!) “real world”.

Their model of intimate heterosexual relationships is one in which the man is an emotionally closed-off provider, and what he wants from a woman is traditional beauty, an extremely limited sexual past (ideally, none), silence, obedience — things like that. And this seems to me to be an outgrowth of the monomaniacal trashworldian focus on others’ immediate approval. You want the best-looking mate you can have, so that others think highly of you. But you’re not really creating anything of value — like, you’re not teaching kids or saving lives or spending years on impactful works of art or engineering. You’re hustling, or creating content, or farming clicks or whatever. So you can’t be with someone who’s aspiring to more than that, compared to whom you might look bad. And you can’t have someone who would ever judge you for putting so much effort into this trivial stuff — and not someone who’d argue with you and show that your ideas don’t stand up to scrutiny. You want the relationship equivalent of a zoned-out border guard who checks your papers and waives you through.

Trashworld creates a certain kind of person, then — one who pursues certain occupations, holds certain ideas and symbols in esteem, and hews to a certain model of relationships, both romantic and otherwise. And it’s my contention — although I won’t argue for it here — that this is not a very good kind of person to be. This kind of person is cold-hearted, and philistine, and fearful, and despite the rhetoric about “hustling”, also lazy. The American-style university is valuable in 2025 largely because, at its best, it produces a different kind of person, or at least makes it harder for trashworld to crank out people in its preferred mold. The university is a counterweight to trashworld, or at least, it can be, and it is better insofar as it is. If trashworld says, implicitly, “Others’ immediate approval and attention are the measure of all things”, the university says “No, some things are great even if very few people like or understand them, and we must bring ourselves up to meet them, rather than dismiss them because they do not stoop to meet us.”

My sense is that this is not a popular way to think of universities these days. It’s much more common to see the core purpose of the university as the transmission of knowledge, with everything else as this weird appendage that we endure and roll our eyes at — the football games, the academic regalia, the winter formals, the student pranks, the ornate lecture halls, the tweed jackets, the streaking, and all of that. Many of us professor-types want to think that we are pure lovers of knowledge, with concern only for the truth about mind, value, reality, which we would pursue even in a dark cinder-block room with no recognition or aesthetic component or anything — sort of like the ideal of the religious believer who communes with God with no assistance from the clergy, or the house of worship, or through music or art. It’s, I guess, not as cool or elevated or hardcore or whatever to need these buttresses.

But the thing is: Most of us do need them. And if the universities don’t give young people what they need, they’ll get it elsewhere, and these days elsewhere is trashworld. Trashworld gives you a model of what men and women and relations therebetween should look like, and this draws you in. It has its own aesthetic, which draws people in. A good aesthetic? Well, I don’t know. I’d like a Bugatti, wouldn’t you? It promises money, and status. “But that’s not real status.” Says who? Coursera? EdX? They don’t take a stand on such matters, and an “IRL MOOC” university doesn’t, either. Universities need these “weird appendages”, then, on pain of being unable to compete with the unified hegemon that is trashworld, and ideally those appendages would not only make the university more appealing, but would, in their own oblique ways, directly reinforce the central value premise of the university. (Even the fonts matter — contrast your average trashworld website logo: clean, no serifs, probably like black and gold — with the blocky Wisconsin “W” or the scripted Alabama “A”. You can picture them right now if you’ve ever watched college football, I’m sure. These fonts are most definitely “out”, and trashworld ones “in”, according to marketers, but that’s kinda the point. These fonts express the core of the university, properly stewarded: We don’t care what’s in or out. That’s not what we do here.)

And this is why, as a great poet of desire once put it, I want all that stupid old shit — homecoming and gothic lecture halls and all that. (I keep trying to get my university to throw a semi-formal on Valentine’s Day, in addition to the usual fare of sexual assault education, so that our students can have good, non-trashworld peer relationships with letters and sodas, but to no avail…) The drive to identify some kind of narrow, specifically cognitive or pedagogical “purpose” and cut out everything that doesn’t advance that misses much of what makes the university valuable, and makes it much weaker as an institution that actually stands a chance of shaping society. It’s even too much of a concession to this narrow way of thinking to outline the distinct roles played by winter formals, and college sports, and tailgating, and mascots, and mottos. Sometimes it’s more obvious that the confluence of factors is having a desirable effect than it is which effects are being had by which factors. And we know its valuable because there is a recognizable mythology associated with the university, and people buy into that mythology with their time, their money, their efforts and their identities. In assessing the value of the university, then, we should keep in mind that institutions typically evolve as they do because they work, and we subject them to the scythe of bean-counting rationality at our peril.6 It’s not as though I think conscious reform is always unwise, but I do think it can’t proceed without an honest accounting of real human needs — to be welcomed, to be a part of something that garners esteem, to be uplifted and awed.

Well, at least the ones paying for my courses…

Now at this point, you might be thinking “Wow, Andrew, it’s amazing that you know, like, random Swiss bridges and who designed them. You must be the kind of guy who only listens to late Bartok and wears different driving gloves for different cars. Not quite: Even though I entered college as an mechanical and aerospace engineering major before switching to philosophy, I still wussed out and satisfied my science and engineering credit by taking this gut/bird course about bridges, which required very little math, and from which I retained very little except for the brilliance of Robert Maillart. And this was at gosh darn Princeton, btw. Figured I owed you that much honesty in an essay like this.

Not really.

All of this should be inside scare quotes to indicate reference to an ideology within which these are buzzwords, as opposed to the things themselves; I like entrepreneurship! I hate trauma!

For more on this, see Michael Oakeshott, “Rationalism in Politics”.

I think I’ve been thinking about this same distinction in a slightly different way. If a bunch of people start doing some weird sort of thing, and if they mainly seek each other’s approval, then they’ll start identifying deep and real features that improve their process. It doesn’t matter if these people are doing pottery or history or poetry or physics, by working mainly for the approval of an audience that they know is also engaged in the same (or a related) project, they’ll make some progress in it. But if they primarily look for the immediate approval of masses of people who haven’t done anything like this before, they’ll produce trash, with some superficial glitz, but without developing real style or content.

If you’re too caught up in only peer review within the community, then the community can spiral out in extreme ways and produce things that no one cares about. But if you’ve got many different communities of this sort, with slight overlaps, each working for their own peers, then a community that spirals out too far gets cut off or pulled back.

When I was at the new faculty event with the chancellor two years ago, he talked about a vision of the university as a place where all kinds of excellence are pursued - and suddenly it makes sense that there would be sports teams and an orchestra as well as historians and physicists.

Excellent piece. Great—even merely good—universities offer genuine community, and that is something distinct from mass lecture and warning labels on everything.