Why I'm a Consequentialist

Warning: Contains original arguments...and cartoons!

What brings people to accept consequentialism? Too much to drink? Lesions to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex? Psychopathy? Or…Divine Grace? (I don’t have a citation to this last one, bc of I think philistine scientism, idk)

In this post, I thought I’d share a bit about what most attracts me to consequentialism. These are my own original arguments, but I think of them as theoretical expressions of some very basic and common intimations of right and wrong. The first is that non-consequentialist moral theories assign fundamental moral significance to things that seem very far from the nexus of mentality, basic agency, and patiency that morality really seems to be about. The second is that our tendency to assign significance to such things seems to be the result of evolutionary, developmental, and other processes that we have good reason to think would yield mistaken moral judgments.

***Lemme say, before I continue — Sometimes I write these posts imagining that I’ll then take a faux-theatrical bow and disappear behind a heavy velvet curtain, put on a silk robe a la Robert de Niro in Casino, and drink Dom Perignon straight from the bottle; for this one, I’m feeling like I want to mix it up a little more, so if you disagree or don’t know wtf I’m talking about or otherwise want to rumble in the comments, I’d love it.***

I. Bad Rationalizations: Meta-Ethics and Action Theory

There’s a Josh Greene paper called “The Secret Joke of Kant’s Soul” (title borrowed from observation/speculation/diss of Nietzsche’s) in which Greene suggests that the grand philosophical arguments for non-consequentialism are mere rationalizations of moral beliefs that were formed and are being sustained by processes other than following these arguments to their conclusions. Well, I’m pretty sympathetic to this speculation of Greene’s; but I’m especially sympathetic to it when the arguments are those drawn from meta-ethics and action theory. That’s why I’m not going to talk about such arguments in the main body of this post — because I really do think they’re after-the-fact rationalizations. Still, I want to lay my cards on the table wrt. the bearing, or lack thereof, of such considerations on good ol’ normative ethics.

But long story short: I’m what they call a meta-ethical “quietist”. And so I don’t think that first-order normative ethics needs any kind of foundation or justification having to do with moral metaphysics, moral semantics, or anything else in meta-ethics, nor do I even think it can have such a justification. So any argument which is all like “Meaning determines extension/proper application; use determines meaning; and we use the term wrong to refer to lying, killing, etc., not just to behaving such that there are bad consequences”, is one that I’ll want to reject. Mutatis mutandis for arguments about causal regulation and reference, or reduction/naturalization of ethical properties, etc. I think anyone who is tempted by these sorts of arguments — i.e. arguments in which normative-ethical theorizing is being steered by metaphysical, semantic, or other extra-ethical considerations — is just badly mistaken about the nature of normative-ethical inquiry and debate.

As to action theory: I mean there’s so much to say here, but I really have two beefs with action-theoretic approaches to ethics. The first is that I think (speculate, guess, whatevs…) that arguments that try to derive ethics from what is constitutive of action appeal to some people largely on the grounds that these people think such moves provide a necessary extra-ethical foundation for ethics. But as I just said, I don’t think ethics needs or admits of such a foundation, and so to my mind, this appeal is illusory. The second is that I think that there’s a certain sense in which acting well is not at all important…

…?…??…???…

…Naw, for real. So some people really, really bear down on this idea that (a) just as something can be good qua chess move, or good qua romantic overture, something can be good qua action, (b) that this standard of goodness qua action is the most authoritative standard in ethics, and that (c) discovering what’s good qua action requires figuring out something like the nature or essence of action; they’ll talk about why action is “dialectical activity” or “self-constitution” and not essentially “world-making” or “production”.1 This strategy does not lead one inexorably towards non-consequentialism, although there are deep reasons I won’t bore you with here why it’s “friendly” to it. In any case, as I’ve argued elsewhere, I’m not on board, basically because I don’t think that goodness qua action, which we can apprehend only once we understand the nature or whatev of action, is the most authoritative evaluative standard. I think that this standard is just plain old goodness, not qua anything, or maybe just goodness qua thing if you’re really into qua’s. Don’t get me wrong — action’s cool and all; you can control it with your will, which is nice; wish I could say that same thing about the line at the DMV (waka waka waka…), but nothing about action’s “nature” or “essence” or “point” bears on the matter of what is the most authoritative standard to which it is subject — just as nothing about a blender’s essence or point is relevant to what, as a matter of fundamental, authoritative normativity, it’s good to use it for.

II. Non-Consequentialism Assigns Value to Irrelevant Stuff

Many of us have had the experience of making moral judgments only to then curl up in embarrassment when we see that these judgments were sensitive to irrelevant factors. Like…order effects! — people are sensitive to the gosh dang order in which scenarios are presented! Or consider that most subjects in Greene et. al.’s experiment thought it was wrong to push the fat man in front of the trolley, while substantially fewer thought it was wrong open a trap door under him by remote control.

But on reflection, it just seems obvious that this is a distinction without a moral difference. When we do harm, it doesn’t matter, ceteris paribus, whether we physically make contact with the other person’s body — and really, “physical contact” is just folk-physics bullshit anyway. At the fundamental level, the little thingies that make up the pusher’s body are no more touching the thingies that make up the pushee’s body than they are making contact with the constituents of Kim Jong Un’s body.

And the “ceteris paribus” (“all else being equal”, for you cool kids out there) is key. Maybe it’s especially bad in some way to directly experience the warmth of the other’s body, the beating of the other’s heart, to look into the other’s eyes and see the glee and the sadness and the toil and blabbity blah, and then push the other off of the footbridge anyway; but of course you can directly experience all of that and then just click the button on the remote control, too, right? (“I feel really connected to you, too; I can’t believe this is only our first date…wait, what’s that device you’ve got there…”)

Well part of why I’m a consequentialist is that I think non-consequentialism assigns moral significance to, as I like to call it, “merely mechanistic” stuff, stuff divorced from the nexus of mentality and basic agency and patiency. The directness of physical relation to the guy plummeting down to the tracks is part of this stuff, but so are things that have gained more of a sinecure in respectable moral theory. For example, the difference between the causal path through which the one person is harmed and the five saved in the pushing and trapdoor cases, and the structure through which the one is harmed and the five saved in the well-known “switch” case, seems likewise mechanistic, divorced from mentality and basic agency and patiency, and as such irrelevant. So, too, is the difference between cases in which most of us would ascribe causality, like drowning someone, and cases in which most of us would ascribe non-causal, but control-involving counterfactual dependence, like failing to save someone from being drowned. All of these seem like differences in the physical manner or path through which agents exert control over patients, and all seem irrelevant.

Now, I obviously haven’t gone through every possible non-consequentialist principle and showed how it assigns fundamental significance to something merely mechanistic like this. And I’m not going to in a Substack post, because that would be like performing a free-form jazz exploration in front of a festival crowd. But basically, I’m optimistic that further investigations into various non-consequentialists’ claims re: the determinants of fundamental moral value would yield more of the same. Also, I guess I just look at what separates consequentialism from non-consequentialism — i.e. the difference between something’s being, broadly, a consequence (or expected consequence, whatevs) of an action, and it’s being, narrowly, something that is linked to action in a particular way that goes beyond just being a consequence, and I think — yeah, that’s all just mere mechanism. Interesting from an engineering standpoint, but not relevant to fundamental moral theory.

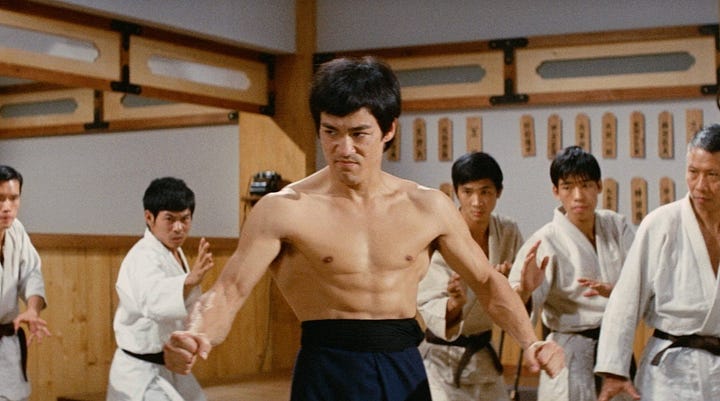

And really, I don’t see what could sway me from this way of looking at things. I mean, I’m walking around acting on the basis of intuitions/seemings/whatever that all the non-consequentialists are. And yeah, some of my best friends are non-consequentialists. But as we’ll see in the next section, I think that all of my/our intuitions to that effect are eminently debunkable — that they can be shown to be the products of evolutionary or developmental processes that “spit out” non-consequentialist judgments in light of factors that seem to have nothing to do with the moral truth. So I don’t place a lot of faith in those judgments. And then once this “mere mechanism doesn’t matter” intuition enters the Battle Royal, it just kind of levels everything else, like Brock Lesnar jumping in the ring against a group of kindergarteners.

And it’s not even just that mere mechanism doesn’t matter; it’s that I don’t see how it could matter, fundamentally. (Maybe it’s best to have social or legal standards that assign significance to causal manner or structure or causation vs. control-involving counterfactual dependence; I don’t know, I’m not a social engineer.) Quassim Cassam has observed that “how-possible” questions arise when we encounter some apparent obstacle to possibility. Well, I think not belonging to the realm of mentality, basic agency, and patiency is an apparent obstacle to the possibility that mechanistic features like the aforementioned are fundamentally morally significant, and I just see no way of surmounting this obstacle. And here my spade is turned. I really cannot envisage the soundness of any argument that has as its conclusion that such mechanistic features are fundamentally significant.2

III. Debunking Non-Consequentialism

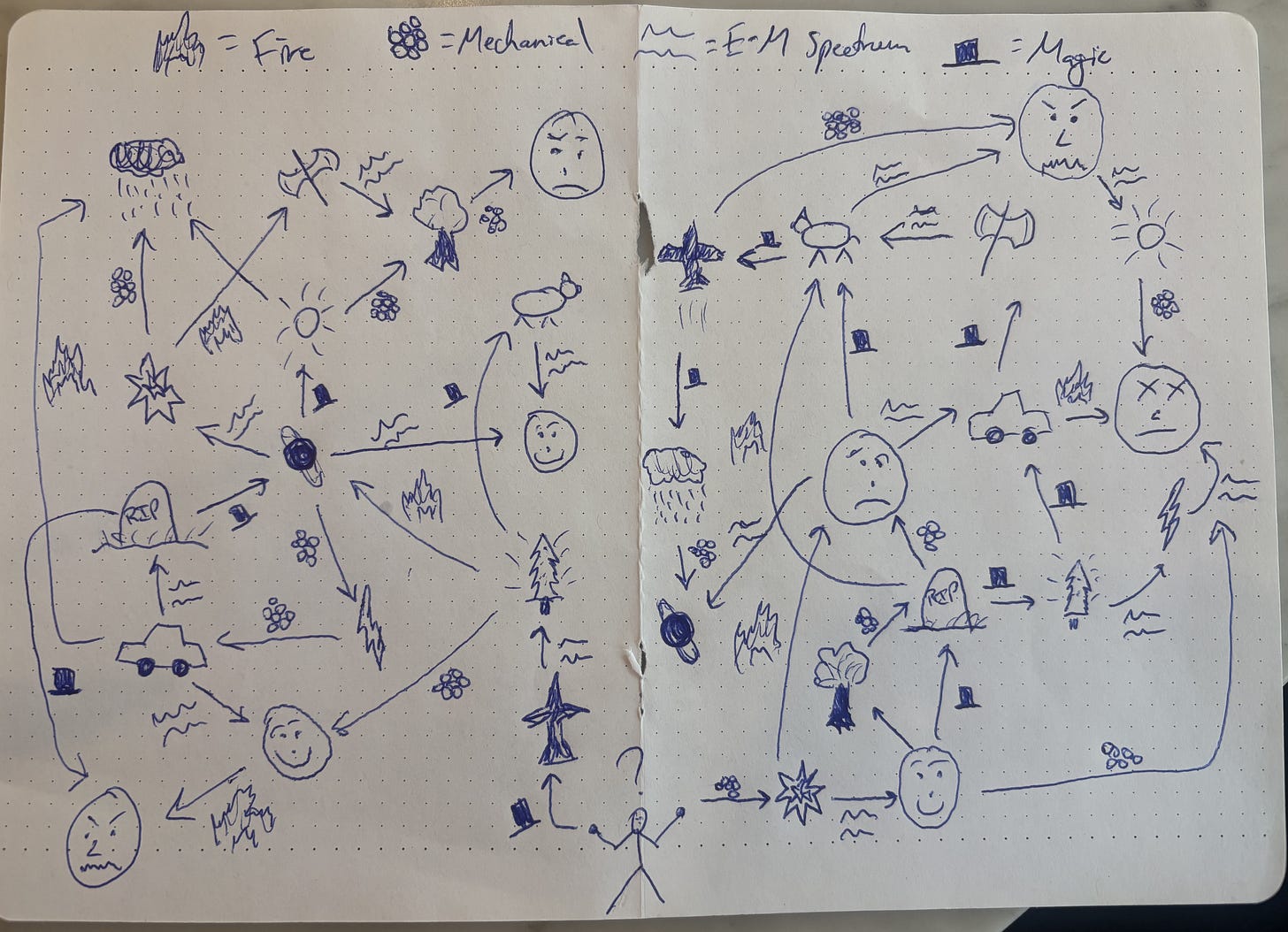

I gave some examples of pertinent debunking arguments in this other post. One argument started with the claim that we evolved to treat harmful actions as fundamentally worse than harmful omissions are because evidence that the former have occurred is more manifest than evidence that the latter have, and so it is extra-advantageous to (a) avoid doing the former, and (b) blame and punish and all that stuff when others do the former. Another set of arguments began with the idea that many non-consequentialist judgments are attributable to model-free reinforcement learning, and such learning in humans has some features that are notable for our purposes — e.g. that it can assign value or disvalue only to very simple, “motor” representations of actions; that during early childhood learning, we come upon very few easily-recognizable instances of harmful omissions and many more of harmful actions. I think that these empirical premises are at the very least plausible, and I think that if they are true, then they cast doubt on the judgments that issue from these processes. We have no reason to believe, for instance, that a syntactic or semantic limitation on a system’s representation of actions is just the right sauce to push that system in a truth-conducive direction. It seems, rather, like a biasing influence.

Now, I find that it is very common for people to dismiss these arguments like Covid in late 2019 — “Oh, it’s probably not that bad, and anyway, it’ll never make its way here”. They think that there’s inadequate evidence for the particular empirical premises, and that even if these debunking arguments manage to pick off a few non-consequentialist (or if we must, “deontological”) principles, there are still more, better ones that are safe from the gathering storm. “Oh, doing and allowing? Nobody believes in that, it’s about starting a new threat vs. redirecting an old one! The Doctrine of Double Effect? What is this, the 13th Century? We have the Principle of Productive Purity! And the revised version with an asterisk! And there are more asterisks where that came from so don’t even start! We can crank out asterisks faster than you can crank out fMRI results, that’s for damn sure!”

Fair play. So why am I so sanguine about this debunking strategy? Well, as I see it, the moral-judgment-forming processes that serve as the starting points for these debunking arguments all have the same feature, and there are good reasons to think that, due to efficiency-related pressures, most every moral-belief-forming process other than explicit reflection and debate will have the same feature. The feature, a conjunctive one, is that:

(a) what these processes crank out are judgments about fundamental moral quality — not about the general usefulness of making certain judgments, not about certain moral rules being helpful as “rules of thumb”, but about what is right, or wrong, or reason-giving, and not merely instrumentally so;

but also:

(b) these processes crank out the judgments about fundamental morality that they do in virtue of features that seem unrelated to fundamental morality — availability of evidence regarding whether some behaviour occurred, limitations on the complexity of action-representations, and so on.

Because, the thing is, explicit moral reflection and debate are capable of fine-grained distinctions; they’re playing on a rich conceptual chessboard. We can say: “Oh, this isn’t fundamentally wrong, but we’re always so strapped for time, so it’s a good policy to just treat it as though it is” or “Yeah, the truth about the matter is such-and-such, but that’s really hard to communicate and build policy around, so let’s focus on something more tractable” or “Yeah, this is no worse than that at the end of the day, but a policy of punishing for this is workable whereas a policy of punishing for that is destabilizing”. But this is nuanced stuff — beyond what a 15-month-old, or our distant evolutionary ancestors, or certain cortico-striatal loops in even the most brilliant of us, are capable of. They can’t crank out shit like that. It’s just not in ‘em. They can crank out plain old “This good, this better, this bad, this worse” judgments, and that’s it. And when that’s all you can do, the only response to any situation or problem, it’s all but inevitable that there’ll be over-ascriptions of fundamental moral significance.

IV. Conclusion and Cartoons

I realize that there are all sorts of arguments for and against consequentialism in the literature — that it can “handle” this case, can’t “handle” that one, that belief in it would result, or not result, from some idealized bargaining process, that there’s a deep theoretical intuition that action should be productive, and so on, and so on. But yeah, for me the basic reasoning is what I gave above. There are details to be worked out and precisifications to be made and counter-arguments to be wrestled with, and maybe we’ll do that in the comments, but it’s really all about the following, for me:

(i) No argument rooted in moral semantics or moral metaphysics or what’s constitutive of action or any of that stuff is going to cut any ice, so just toss all them out. It’s just regular, first-order ethics all the way, no possibility of getting “outside” of it or looking at it from “sideways on” or what-have-you.

(ii) Non-consequentialism assigns fundamental significance either directly or indirectly to these merely mechanistic features — causal manner or structure and so on down the line, and there’s just nothing I’m more confident about in ethical theory than that all that stuff doesn’t matter. I’m a pretty open-minded dude; for almost any ethical judgment, I don’t want to close the door on the possibility that it might be correct, some way, somehow. But as far as the judgment that some merely mechanistic feature might be a bearer of fundamental moral significance? — I do want to close that door, I must say; there’s no way to answer the “how-possible” question.

(iii) “Yeah, but what about all of the smarter-than-you moral philosophers who don’t accept what you’re so confident about — not to mention the folk, THE FOLK, Andrew, doing their little Morris dances and fighting off Wyverns and shit?” Bah, I say let the Wyverns have th…oh, sorry, sorry, that’s not the response I want. The response I want is that I’m very sanguine that all of their moral intuitions that imply the contrary are debunkable……So yeah, fuck it:

𝕷𝖊𝖙 𝕿𝖍𝖊 𝖂ÿ𝖛𝖊𝖗𝖓𝖘 𝕳𝖆𝖛̈𝖊 𝕿𝖍𝖊𝖒

Okay, who wants cartoons?

Enjoy!

See Talbot Brewer, The Retrieval of Ethics, and Christine Korsgaard, Self-Constitution, respectively. These are really good books, btw, and Brewer’s is really underappreciated. (Just wanted to say that, so people don’t think I’m just some cocky asshole.)

When I finished writing this piece, I ran it through ChatGPT and Claude to get their assessments. ChatGPT was all like “nobody understands you like I do, baby, we’re too pure for this world”, but Claude kinda thought I was being a cocky asshole, just a lil’ bit, and also that this first section about mechanism was more assertion than argument. And I guess that’s true. But one thing that I think it’s really important to internalize as a philosopher is that explanatory power and dialectical power can, and often do, come apart. The arguments for a theory that might work the best at bringing neutral or hostile interlocutors over to your side may well not explain why the theory is correct. And so, in this context, it may be that the most dialectically effective arguments would be kinda underlabour-y attempts to show that consequentialism can “avoid” this result or “capture” that intuition; or they may be clever arguments that only consequentialism can satisfactorily handle examples involving supertasking or uncertainty; or they may be really ingenious ones like Holly Smith’s argument that non-consequentialism has difficulty explaining the importance of gathering more information before acting. But none of these would, to my mind, be a deep explanation of why consequentialism is correct. But that’s what I’m trying to offer here. Will it convince many people? Don’t know, don’t really care. Am I worried that there are really smart, good-hearted people who remain unconvinced — worried enough that I am inclined to suspend judgment on the basis of higher-order evidence provided by their disagreement? No, and this is for the reasons provided in the next section. Hope that helps!

Great post!

I’m a deontologist, but a non-Kammian one. Like you, I don’t think doing/allowing (etc.) is an intrinsically morally significant distinction. But that’s because I think what matters is not violating rights. The contours of rights are sometimes squiggly and arbitrary, because we have to be able to coordinate on them. So I find trolleyology a low-priority exercise (though it was worth it to discover that there *isn’t* some clear and attractive principle at work). And yet I still like rights.

In fact, I’d still like rights even if I were a consequentialist! I’d just think of them as akin to “secondary principles” rather than being intrinsically important.

Thanks for this interesting post!!!

A consequentialist with a sufficiently capacious axiology may need to recognize that sometimes the "mechanical" stuff matters because it is constitutive of some value or other (achievement, Autonomy, what have you). That's not yet saying that it can matter in the distinctive way that non consequentialists want, but if a consequentialist is willing to go that far, then the intuition that mechanism doesn't matter *in the particular way that non-consequentialists have in mind* seems pretty fine-grained and contestable.